Reflections from Aspen Institute's Socrates Seminar

Three days of philosophical inquiry on whether AI brings a "New Enlightenment or Digital Despotism," with Cosmos and the Aspen Institute

This is a guest post from Ashley Kim, a computational scientist and philosophy graduate student who participated in the seminar and is part of the Cosmos team.

Sapere Aude — “Dare to know.” Kant made this the motto of the Enlightenment, borrowed from the Roman poet Horace. For Kant, it meant humanity's emergence from “self-imposed immaturity,” our reliance on others to think for us.

But three centuries later, we face puzzles Kant never anticipated. What happens when the tools meant to enhance human reason now risk replacing it? What if the greatest threat isn’t ignorance, but knowledge itself—discoveries that could destroy the very civilization that produced them? And in attempting to manage these risks, are we recreating the same immaturity Kant warned against?

These questions drove three days of discussion at the Socrates Program seminar, “Will AI Bring A New Enlightenment or Digital Despotism?” hosted by the Aspen Institute and moderated by Cosmos founder Brendan McCord.

The stakes are high. Enlightenment promises autonomy: the capacity to think and choose independently. But digital despotism offers something seductive: the gentle management of all our choices by systems that know us better than we know ourselves.

Thinkers from across disciplines gathered to test these possibilities. What emerged were insights about preserving human autonomy while harnessing AI, and warnings about the subtle ways we might lose ourselves in the process.

And perhaps most important, a call to action. When Horace first wrote “Dare to know,” he added something Kant left out: “Begin!” — incipe. Like Kant, let’s look to the wisdom before us and then answer it with action. The future depends on what we build now.

If you’d like to join a future seminar on philosophy and AI with Cosmos Institute please fill out our expression of interest below.

Session 1: Philosophical Foundations – Autonomy · Truth‑Seeking · Decentralization

The first day established the philosophical stakes. If AI is to serve human flourishing, we need clarity about what we're trying to preserve. We focused on three key goods: autonomy, truth-seeking, and decentralization.

Autonomy

Kant's insight was as much psychological as political. Most people avoid the hard work of independent judgment. “It is so convenient to be a minor,” he observed. We prefer letting others decide for us: priests, experts, and now algorithms.

Tocqueville saw how this tendency manifests in democratic societies. Citizens become isolated and overwhelmed by choice. Bureaucratic control promises to manage their decisions, and they eventually trade autonomy for comfort. This soft despotism doesn't crush human will; it renders it obsolete.

Both philosophers understood that autonomy requires cultivation and responsibility. It's not just freedom from external constraint, but a purpose-driven, inner capacity for self-direction—one that atrophies without use.

Key discussion question:

Kant described his era as one of “Enlightenment, but not yet Enlightened.” How does ours compare? We’ve achieved great developments in governance, technology, and the expansion of public discourse, but are we better now at autonomous reasoning?

Core readings:

Immanuel Kant, “What is Enlightenment?” (link)

Alexis de Tocqueville, “What Kind of Despotism Democratic Nations Have to Fear,” Democracy in America (link)

Also see:

Wilhelm von Humboldt, “Ch. 2: Of the Individual Man and the Highest Ends of his Existence,” in The Sphere and Duties of Government (link)

Leon Kass, “The Problem of Technology,” Leading a Worthy Life §§1‐4

Truth-seeking

Mill's case for free speech begins with an admission of our limits. No person or institution is infallible enough to silence others, and complex questions rarely yield a single point of view. Instead, truth emerges from contestation, as opposing perspectives collide and expose what’s worth keeping. Mill argues that even wrong or unpopular opinions contain “shards of insight” essential for deeper understanding: “the peculiar evil of silencing the expression of an opinion is that it is robbing the human race.”

Mill also warns of leaving beliefs unchallenged, even true ones. Without ongoing debate and exposure to opposing views, accepted truths lose their vitality, hardening into mere habit rather than reasoned conviction. Famously, he notes that the person who knows only their side of a case “knows little of that.” Unchallenged beliefs also lack the psychological force to motivate action, becoming “dead dogmas”; only ideas that survive genuine opposition retain their power to guide conduct and shape character.

AI systems can amplify echo chambers or break them open, surface minority views or bury them in algorithmic consensus. Mill would ask: do they move us toward truth? Do they make our beliefs more alive or more dead?

Key discussion question:

Mill’s ideal of open inquiry involves sharing not just ideas, but also diverse language, concepts, and patterns of living and thinking. How do we preserve this individuality in an age shaped by generative AI?

Core reading: J.S. Mill, “Ch.2: Of the Liberty of Thought and Discussion,” On Liberty (link)

Also see: Plato, Theaetetus, 149A‐152A; 189A‐190A

Decentralization

Hayek understood progress as an evolutionary, collective process driven by individual liberty. Civilization advances when people pursue their own goals, using their unique knowledge. This includes both explicit propositions and tacit understanding embedded in habits, skills, and local circumstances.

This diversity forms a discovery mechanism: thousands of parallel experiments unfold as individuals test new approaches, adapt to changing conditions, and work toward varied objectives. Market prices, social customs, and institutional practices carry signals that coordinate these efforts without central direction. Success gets copied; failure gets abandoned.

The result is what Hayek called the accumulation of adaptation knowledge: successful routines embedded in tools, practices, and institutions. Each generation inherits this stock of proven solutions and builds upon it, adapting old tools to meet new challenges. Like Mill, Hayek emphasizes humility, arguing that progress is not driven by grand plans, but by “countless humble steps” taken by anonymous individuals, steps that matter as much as the breakthroughs of a Newton or an Einstein.

This process depends on genuine uncertainty and the freedom to fail. Innovation requires the constellation of aptitudes and circumstances that no authority can foresee or arrange; if outcomes become predictable, the discovery mechanism breaks.

The challenge for AI is preserving this evolutionary dynamic. Do these systems enhance human capacity for experimentation and discovery, or do they breed uniformity? Can algorithmic optimization coexist with the unpredictable creativity that drives innovation?

Key discussion questions:

How does Hayek’s view of dispersed knowledge relate to modern AI, where models aggregate contributions from many individuals, but often return a single perspective?

Is increased reliance on AI making humans more predictable? If so, do we face a kind of civilizational standstill—one in which the conditions for genuine discovery and innovation begin to fade?

Core reading: F. A. Hayek, “Ch.2: Creative Powers of a Free Civilization,” Constitution of Liberty

Also see: Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France, Paras. 1‐42, 1790

Session 2: Visions of the future – how dominant views frame risk, value, and progress

The second day confronted a stark question: How should we respond to technologies that could transform, or even destroy, civilization? We considered several distinct visions, each offering different answers about risk, progress, and the role of human autonomy in an age of AI.

Doomsayers

Nick Bostrom's “vulnerable world hypothesis” represents a new genre of philosophical reasoning that fuses three elements: Bayesian uncertainty, normative minimalism (survival above all), and political maximalism (global governance and surveillance).

His central metaphor is an urn of possible discoveries: most balls are white (beneficial), some gray (mixed), but at least one may be black—a technology that, once discovered, destroys civilization.

This isn't traditional risk assessment, but a claim about technological development itself. Bostrom argues that if black balls exist and we lack governance to suppress them, catastrophe becomes statistically inevitable. His solution? A “precautionary panopticon”: global surveillance capable of detecting and stopping dangerous discoveries before they spread. Bostrom reverses the liberal default, where freedom is assumed until specific restrictions are justified; in his framework, potentially dangerous inquiry is prohibited until proven safe. This represents a kind of "Pascal's wager in secular terms"—betting on totalizing surveillance to avoid infinite loss.

A deeper challenge concerns unknowable futures. Traditional economics distinguishes risk (rolling dice) from uncertainty (genuinely unpredictable events). Bostrom collapses this distinction by treating the mere possibility of black balls as sufficient grounds for preemptive control, transforming uncertain futures into palpable scenarios requiring drastic governance.

The bind is that if technological development is predictable enough to model with urns, perhaps we can govern it without resorting to surveillance. But if it's so unpredictable that we might destroy ourselves at random, then probabilistic modeling breaks down. Bostrom relies on uncertainty to justify alarm—yet on predictability to justify his solutions.

Key discussion questions:

Bostrom's precautionary panopticon offers safety through total surveillance—but at what cost? How do we balance security and liberty when existential fears threaten freedoms essential to human flourishing? At what point does preventing dystopia become dystopia?

If acceleration carries existential risk, does deceleration carry greater risk? What if the technologies we refuse to build—advanced medicine, space colonization, climate engineering—are precisely what we need to survive?

Core reading: Nick Bostrom, “The Vulnerable World Hypothesis” (link)

Also see:

Will MacAskill’s “What We Owe the Future” pp 11-25

Eliezer Yudkowsky “AGI Ruin: A List of Lethalities” (link)

Responses to Bostrom’s Vulnerable World Hypothesis from David Deutsch and Robin Hanson.

Accelerationists

Marc Andreessen's “Techno-Optimist Manifesto” reads like a secular gospel for Silicon Valley: part philosophical treatise, part war cry against what he sees as civilizational stagnation. Its main contention: “Everything good is downstream of growth.” Societies are like sharks; they must move forward, or perish.

Technology becomes the prime moral force of history. It’s not just useful, but redemptive. It is “the glory of human ambition and achievement, the spearhead of progress, and the realization of our potential.” “Advancing technology is one of the most virtuous things that we can do.” Markets are discovery engines that align self-interest with collective benefit. AI is the ultimate force multiplier for solving humanity's greatest challenges. And progress is a moral imperative. “We believe any deceleration of AI will cost lives. Deaths that were preventable by the AI that was prevented from existing is a form of murder.”

Andreessen oscillates between two views that are in tension: technology as tool (guided by human choice) and technology as autonomous force (an unstoppable “optimization process”). If it’s the former, it requires moral judgment and potentially restraint. If it’s the latter, moral considerations get displaced by a dogma of pure materialism, in which acceleration is its own justification.

This inconsistency runs deeper than rhetoric. Andreessen aligns himself with classical liberalism, invoking Hayek, markets, and individualism, but abandons the moral architecture that makes liberalism coherent. Classical liberals like Locke and Mill grounded value in human dignity and rational equality. They understood that technology, like any tool, is only as good as the ends it serves. Andreessen emphasizes productivity metaphors: values get collapsed to contributions to a growth curve.

Key discussion questions:

Does this view represent a genuine confidence in human agency, or the abandonment of it? If technology follows its own optimization logic, what role remains for human choice?

Andreessen aligns human flourishing with material abundance. But can optimization systems recognize goods that resist measurement—love, beauty, contemplation, play? What happens when efficiency becomes the only virtue we can compute?

Core reading: Marc Andreessen, “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto” (link)

Also see:

Beff Jezos and Bayeslord, “Notes on e/acc principles and tenets” (link)

Nick Land, “Meltdown,” Fanged Noumena, Urbanomic/Sequence Press, 2011 pp. 443 – 451

This response to Marc Andreessen: Yuval Levin “For Whom Shall We Build” (link)

Other readings on visions for AI

Translated excerpts from China’s ‘White Paper on Artificial Intelligence Standardization’” (link)

Markus Anderljung, Joslyn Barnhart, et al.,“Frontier AI Regulation: Managing Emerging Risks to Public Safety” (link)

Emily Bender, Timnit Gebru et al., “On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big?” (link)

This response to top-down controls: From Dean Ball’s Hyperdimensional Substack (link)

Mencius Moldbug, A Gentle Introduction to Unqualified Reservations, §§1‐8

Session 3: Design & Implementation – translating principles into institutions and algorithms

The final day posed a crucial test: Can philosophical ideals take shape in code? Three concrete proposals were discussed, each aiming to translate the goods we explored—autonomy, truth-seeking, decentralization—into working systems.

Design Principles

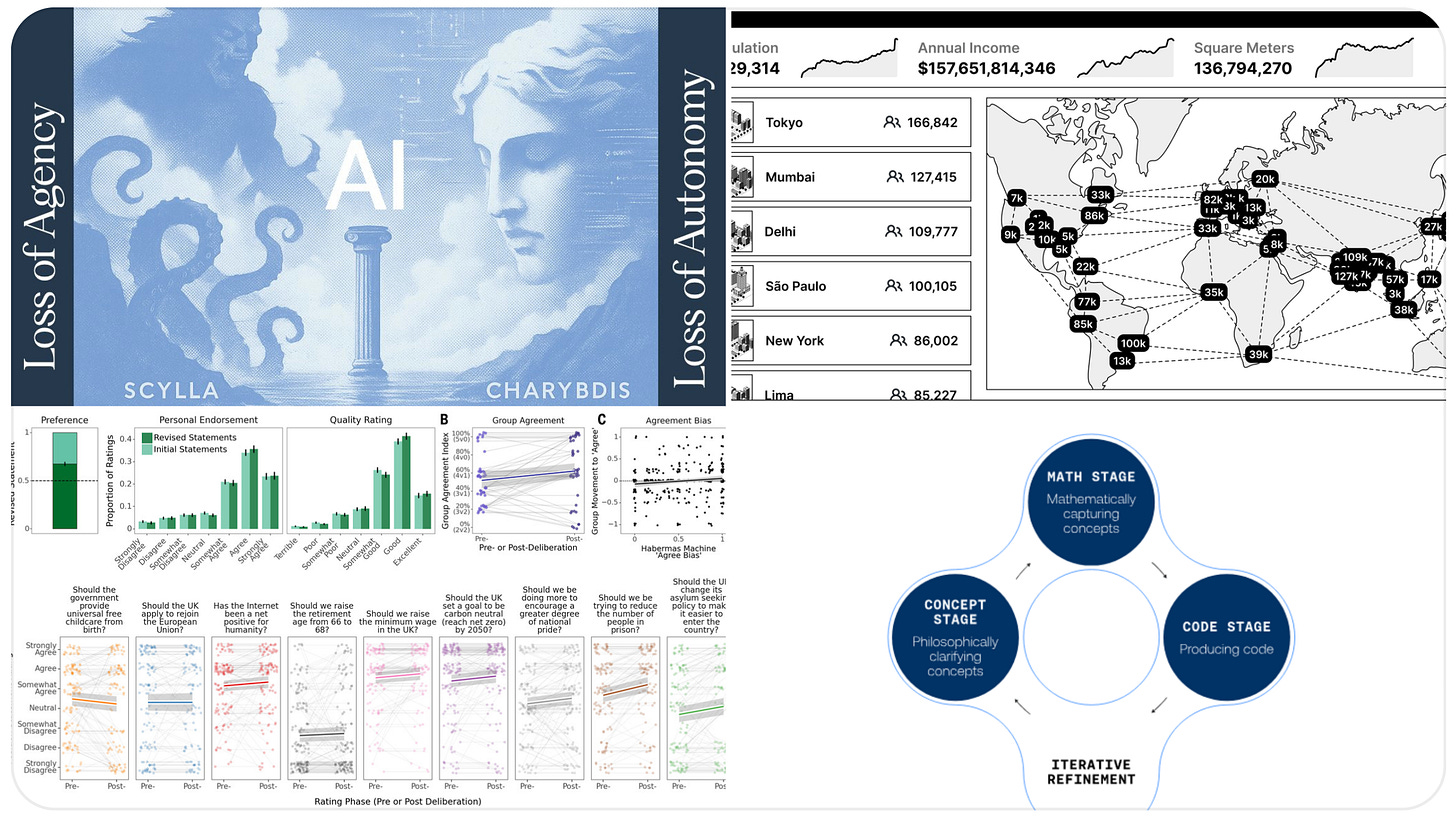

Philipp Koralus diagnosed a modern version of the classical Scylla and Charybdis dilemma. As AI systems become more capable, users face an impossible choice: either drown in complexity (losing agency) or accept algorithmic guidance that subtly steers their decisions (losing autonomy). Current AI operates like Tocqueville's “tutelary power,” managing choices so seamlessly we forget we're being managed.

Koralus proposes an alternative: AI agents that behave like Socratic tutors, a privacy-preserving partner in reason rather than a substitute for it. Instead of providing answers, they surface questions. Instead of optimizing outcomes, they cultivate judgment. Instead of nudging users toward predetermined goals, they help users discover what they actually want and why. Users can remain “authors of their own choices” even as complexity increases.

Key discussion questions:

What qualifies as a “nudge”? If nudges are in some sense everywhere, how do we identify when permissible nudges turn into manipulation?

How can we scale Socratic dialogue without relying on scripted heuristics? If the goal is human autonomy, how do we design questions that guide reflection without becoming another form of gentle control?

Core reading: Philipp Koralus, “The Philosophic Turn for AI Agents: Replacing Centralized Digital Rhetoric with Decentralized Truth‑Seeking” (link)

Institutional architectures

Since the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, the rule has been “first control territory, then claim sovereignty.” Balaji Srinivasan proposes the inverse: start with online communities, build wealth in cyberspace, then crowdfund physical territory.

The mechanics are appealingly startup-like. Form communities on Discord, coordinate through crypto, then publish success metrics on blockchain dashboards. Once you achieve scale and wealth, negotiate with existing states for autonomy. Like Bitcoin, legitimacy comes through adoption rather than traditional politics.

Srinivasan frames this as the ultimate “exit.” Dislike your government? Leave for a community that shares your values. Crypto makes it economically feasible; remote work makes it practically possible.

But the philosophical foundations are shakier than the technical ones. Network states treat political problems as consumer preferences rather than genuine conflicts over justice and the common good. They promise maximum choice while minimizing the friction of disagreement. But how can a system optimized for voluntary participation care for those who cannot easily exit their existing states? And if the most capable citizens leave for better opportunities, what incentive remains to improve conditions for those left behind? Network states might solve governance for the well-connected—while abandoning everyone else to deteriorating legacy institutions.

Key discussion questions:

Hannah Arendt described how stateless people lost basic protections in the 20th century. How would network states handle vulnerable populations who aren't “chosen” for communities? What dangers might this pose?

Who enforces rules or monopolizes legitimate violence in a network state?

Can digital communities support infrastructure and well-being needs that depend on us living with each other in physical communities?

Core reading: Balaji Srinivasan, “The Network State – in One Essay” (link)

Also see:

Jürgen Habermas, Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry a Category of Bourgeois Society

Sam Altman, “The Merge,” 2017 (link)

Deliberative algorithms

DeepMind's “Habermas Machine” aims to scale democratic deliberation using AI mediation. The system uses two components—a statement generator and preference predictor—to craft group consensus statements that maximize approval. In trials with over 5,000 people, AI-generated drafts outperformed human mediators more than half the time.

The promise is scaling genuine deliberation beyond expensive citizen assemblies. Instead of face-to-face dialogue, participants submit opinions and critique AI-generated drafts until consensus emerges.

But this raises questions about what deliberation actually requires. Habermas emphasized that legitimate decisions emerge from the “unforced force of the better argument” in conditions approaching ideal speech. Tocqueville understood that democratic citizenship requires what he called “the reciprocal action of men upon one another”—people engaging directly, learning to cooperate through trial and error. Can algorithmic mediation preserve these conditions?

Key discussion questions:

Does consensus indicate successful truth-seeking? Real deliberation changes minds through encounters with opposing views; algorithmic optimization might find palatable compromises without genuine engagement. What other criteria should we use to assess deliberation quality?

In the Habermas Machine project, participants never actually talk to each other. They interact only through an AI intermediary that translates and synthesizes their positions. How effectively can machines substitute for the human process of mutual recognition that deliberation requires?

Can democracy survive its digital optimization? Or does scaling deliberation destroy what makes it democratic?

Core reading: Michael Henry Tessler, et al., “AI Can Help Humans Find Common Ground in Democratic Deliberation” (link)

Also see:

Christopher Summerfield, et al., “How will Advanced AI Systems Impact Democracy” (link)

Ivan Vendrov et al., “What Are You Optimizing For? Aligning Recommender Systems with Human Values” (link)

Anil Sarkar, “AI Should Challenge, Not Obey” (link)

With thanks to Ashley for sharing her reflections; to everyone who attended for their discussion contributions; and to the Aspen Institute for running the seminar series and for their support and partnership.

If you’d like to join a future seminar on philosophy and AI with Cosmos Institute please fill out our expression of interest below, and stay tuned for learning and discussion opportunities via Substack.

Cosmos Institute is the Academy for Philosopher-Builders, with programs, grants, events, and fellowships for those building AI for human flourishing.

Insightful stuff Ashley!

Its very cool style of writing with different angles. I read second time because first time I don't believed my eyes :))