Autonomy or Empire

Shall we rule our tools, or shall they rule us?

In 1939 New York World’s Fair opened its gates in Queens. Visitors were promised nothing less than the “World of Tomorrow” as they patiently filed through a model metropolis next to a sign that read Democracity. The display showed a miniature city with uniform housing, regimented zoning, and a central hub in the dome’s center. Here, a good city is one where life fits the planner’s design.

Lewis Mumford thought otherwise. Writing in the New Yorker a few weeks later, the American historian argued exhibits like Democracity failed to reckon with the realities of how people actually work and play. For Mumford, to live there meant to accept that every element of existence — where you called home, where you worked, and how you moved — had been decided in advance. Life was organized by design, and the design was totalizing.

Real urban life is dynamic. It’s the sum of competing visions between merchants and manufacturers, planners and politicians, civic groups and neighborhood associations. Streets are contested, zoning is fought over, and new arrivals bring with them their own ideas about the good life. The vitality of the city is the product of this negotiation. In that sense, the New York World’s Fair taught visitors to confuse technological gigantism with a kind of progress commensurate with the dynamic character of Western societies.

The ways we build shape the ways we live. Machines and infrastructures carry with them assumptions about order, scale, and authority, and in time those assumptions become habits of life. Just as a city organized by central command produces a different kind of civic existence than one made through negotiation, so too do technologies that enforce conformity and control produce a different kind of human experience than those that leave room for initiative.

Train of thought

Mumford described some technological forms as “authoritarian” insofar as they concentrated power in large organizations, enforced uniform routines, and suppressed diversity of use. Against them stand “democratic” technologies which tend to be adaptable, small-scale, and embedded in the fabric of human life. Where one compels uniformity, the other fosters variety; where one subordinates people to the system, the other creates systems that allow humans to live on their own terms.

We can think about these modes of development in relation to autonomy, the cultivated capacity to deliberate well about how to live, to revise one’s understanding through experience, and to act on one’s own judgment within a community that recognizes this same capacity in others. Humans develop autonomy through practice and defend it against deterioration, which requires the freedom to make choices and the discipline to reflect on their consequences.

Autonomy is something we all pursue independently, but it’s also something that we enact in negotiation with others. Authoritarian technologies weaken that practice by replacing deliberation with prescription: the road system dictates where you go, the assembly line dictates how you work, the digital platform dictates what you see and when. By contrast, democratic technologies leave room for initiative, improvization, and the feedback of lived experience. They are rarely wholly liberating, but their constraints tend to be outweighed by their positive effect on autonomy.

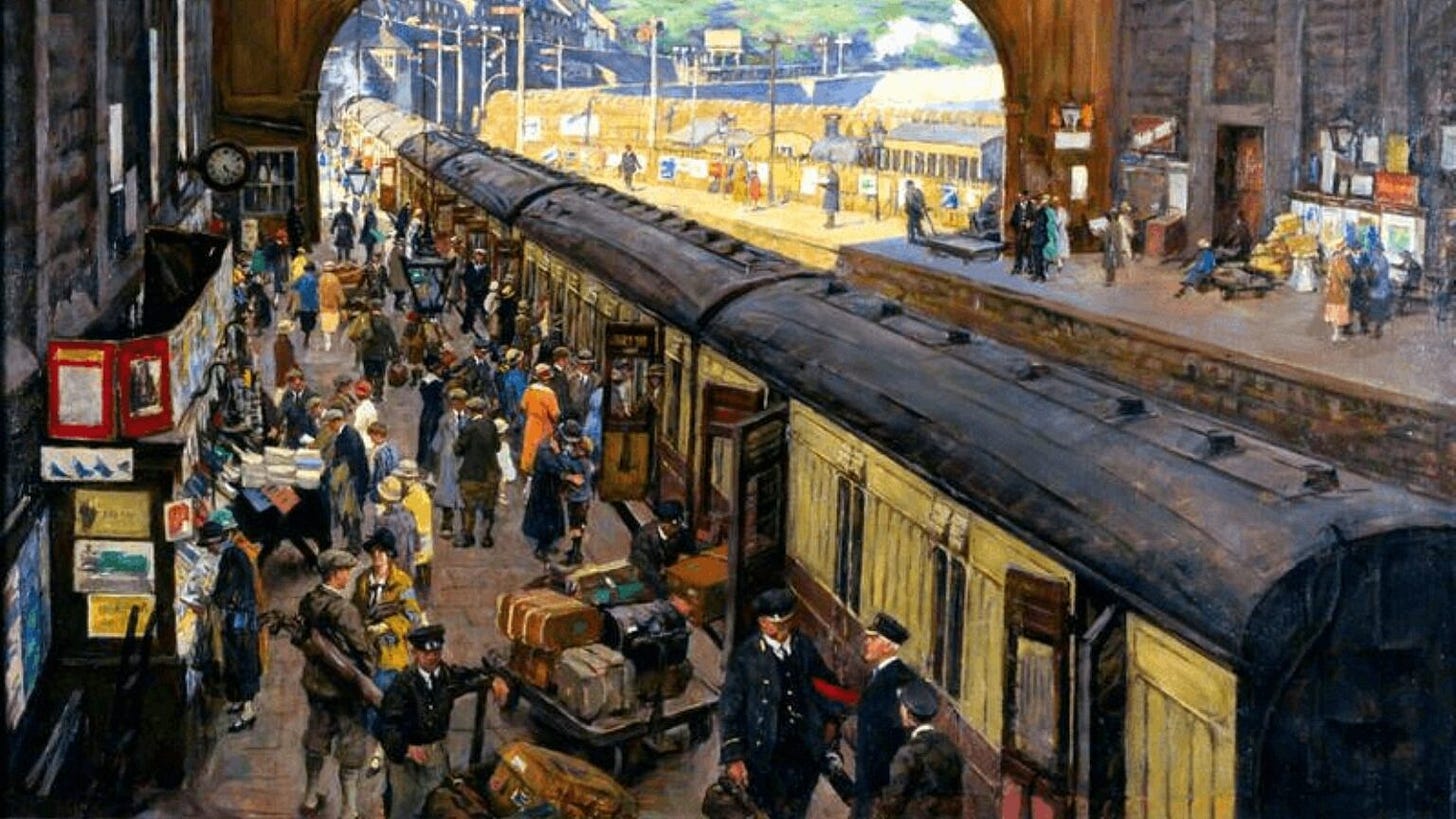

Mumford liked to illustrate this dynamic using the railroad. The locomotive represented a faster means of getting from one place to another, but it also reorganized human life around its timetable. As Henry Thoreau put it in 1854’s Walden, “We do not ride on the railroad; it rides upon us.” What he meant, and what Mumford also saw, was that progress isn’t free. Villages that once kept time by the sun or the church bell found themselves bound to the clock of the railway station. Markets and towns adjusted to the demands of a system that required standardization and predictability.

But railroads were also tools of liberation. They opened mobility to millions, linked distant communities, and spread ideas across the continent. They required centralized coordination, yes, but they also enabled local initiative: farmers could reach new markets, migrants could move inland, and families could visit one another across distances that once made separation permanent.

The political life of technology is governed by the particularities of its design and the context in which it is deployed. In nineteenth-century Russia the railways were built as extensions of the state, radiating from St Petersburg and Moscow to enforce autocracy across a vast empire. Their routes were chosen to move troops quickly, to tie the provinces more tightly to the capital, and to project imperial authority into distant territories.

Railroads in the United States followed a different path. Instead of emanating from a single place, they stretched westward in lines financed by private capital, state subsidies, and land grants. Building and operating them required immense pools of capital, which in turn produced corporations of unprecedented scale. These companies fixed freight rates, lobbied legislatures, and dictated the economic fortunes of entire regions.

The broader point is that technologies are partly socially constructed, that the form they take is contingent on the political, cultural, and economic conditions under which they emerge. There are of course instances of technological development that are more closely connected to the expression of individual vision, but no builder creates in a total vacuum. Most inventions carry both authoritarian and democratic potentials within them. What determines where they settle on that spectrum are institutions that build them, the regulations that channel them, the habits and expectations of the people who use them.

AI, authoritarian and democratic

Our defining technology is AI. Like the railroad in the nineteenth century, it is both a system and system-builder that reorganizes patterns of work and communication. It reaches into classrooms and hospitals, boardrooms and battlefields, altering how decisions are made and by whom. The stakes turn on the shape of autonomy, the essential good that allows people to decide what kind of life they want to live.

To put the matter in Mumford’s terms, AI is a technology with two faces. It can be built and governed in ways that centralize authority, prescribe routines, and render human judgment redundant. Or it can be developed so that its constraints serve human purposes, widening the space for initiative and collective life.

AI systems already make proxy judgments, set defaults, and structure attention in ways that ripple far beyond the screen. They filter the news we see, influence how we travel, and shape how resources are allocated across the economy. In each of these instances what matters is how much space AI leaves for us to exercise judgment in relation to it. A default can guide or it can dictate; a recommendation can widen horizons or it can narrow them.

The difference between authoritarian and democratic technologies is partly about structure, but it’s also about whether they encourage us to make our own decisions. The railroad disciplined life yet enabled individuals to act on their own purposes. AI can pressure autonomy by prescribing choices, or it can bolster it by supporting reflection, improvization, and deliberation.

The AI project carries within it authoritarian and democratic characteristics that can grow or wither according to how these systems are developed and deployed. Its underlying form is today authoritarian in that the most capable models require clusters that cost billions and energy budgets measured in megawatts. Only a handful of corporations and states can command such resources, which means that the direction of the field is set by a small cadre of technical and financial elites.

AI also invites deference, the process by which people outsource their own judgment to the system instead of deciding themselves. Think about diners who only go to the highest rated spots, employers who let resume-screening systems decide which candidates to interview, and last year’s Claude Boys meme, after which people opted to “live by the Claude and die by the Claude.” These represent an authoritarian strain in that in each case autonomy is diminished.

But AI is also in some sense democratic. Unlike other large-scale technologies, AI can be adapted at relatively low cost once an initial model has been trained. Training an open-source system may require significant resources, but fine-tuning on local data or distilling into smaller versions can be done by universities, startups, and even committed hobbyists. This diffusion of capability makes something like a set of tools that can be picked up and reshaped in local contexts.

Anyone with an internet connection can access a best in class AI via a browser or a smartphone. This means its power is not only confined to states or corporations, that anyone can get thousands of queries for $20 a month. Widespread access is an impressive feat, but without control it risks leaving users as consumers of systems they cannot shape. A technology that can be used by the many but governed by a few may democratize access while still concentrating power. The architecture of AI itself can be democratic too, with decentralized training methods showing that the work of building medium-sized models can be spread across many locations.

When AI systems are built in ways that disperse control and encourage initiative, they sustain the practice of autonomy. And when autonomy is preserved, it generates the dynamism needed to keep those systems open and revisable. In an authoritarian form, by contrast, judgment is outsourced and it becomes harder to contest or imagine alternatives.

Our challenge is to build AI so that its democratic tendencies outweigh its authoritarian ones. Maximizing the former means designing systems that are transparent rather than opaque, revisable rather than fixed, and open to adaptation by the people who use them. It means encouraging builders to ask why they want to build as well as what they want to build. And it means cultivating practices of use that treat AI as a partner to be tested, questioned, and improved upon.

Mumford and Sons

Like the railroad, AI will not be defined only by its machinery but by the institutions that govern it. Design choices — whether models are open or closed, adaptable or fixed, and optimized for engagement or deliberation — will shape how much autonomy they leave to their users. Institutional choices, like what pressures builders respond to, will decide whether those technical forms concentrate power or diffuse it.

Technologies have always tempted us with structure, speed, and ease. But the good life isn’t necessarily an easy one. The “world of tomorrow” was one of perfect order, but our world is the stuff of experimentation, disagreement, and revision. Every generation builds tools that promise to lighten its burdens, whether through the perfect plan or the perfect machine. And every generation must answer the same question: shall we rule our tools, or shall they rule us?

Cosmos Institute is the Academy for Philosopher-Builders, technologists building AI for human flourishing. We run fellowships, fund fast prototypes, and host seminars with institutions like Oxford, Aspen Institute, and Liberty Fund.

Technology can enable the systemization of economic activity; the railroad created abundance and economic liberation for towns and cities while also putting chains on these very cities to adhere to the guidance and systemization of the rail system. AI is similar, and the comparison seems to be a good one.

It's so wonderful essay.... Great perspective