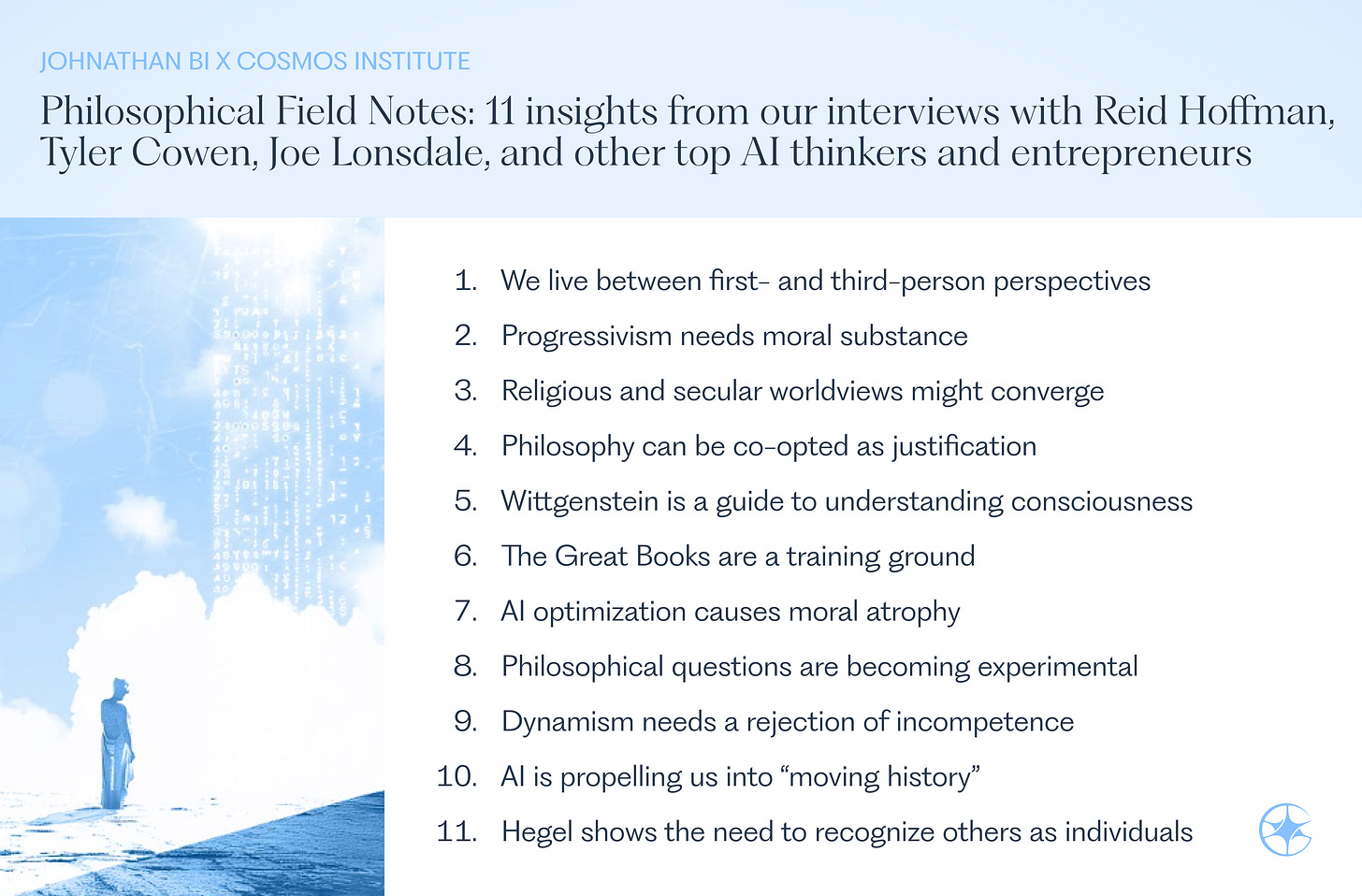

Philosophical Field Notes: 11 Reflections on AI, Technology, and Ourselves

Reid Hoffman, Tyler Cowen, Joe Lonsdale, Nick Bostrom and others get philosophical

What does Hegel have to do with LLMs? Can religious and secular accounts of the good life be reconciled?

In order to build the future well, we believe you need to think deeply and learn from the past.

Over the last year

, working with Cosmos, has interviewed many top thinkers and builders on the intersection of AI, entrepreneurship, and philosophy.We’ve rounded up some of the best insights from the interviews so far. From the “hard problem” of consciousness to the mechanics of liberty, these reflections offer a look into the ideas shaping our technological future.

Note: For upcoming interviews, including conversations with MacKenzie Price and Peter Thiel, subscribe here.

We live between first- and third-person perspectives

Marcus Ryu, Founder of Guidewire, Oxford philosophy BPhil

The difference between the first- and the third-person perspective is the taproot of a whole host of philosophical questions. Including, in my opinion, the deepest, the most unfathomable question of all, which is, how does our mind and subjectivity exist in a material world? It’s the deepest of all mysteries.

But that is also a switch between the first and third person perspectives. I inhabit the world in a particular place, I am situated at a particular locus, and I have a set of experiences that are distinctly, and maybe even privately, mine. But at the same time, I am an observable embodied creature.

I see much of the entrepreneurial journey through this philosophical lens. You have this first person drive, which is, I can only succeed. And you have the third person reality, which is that the world is indifferent, and we could fail, and we probably will… A key part of Hegel is that you don’t know. The participants in history, first of all, they’re expendable. But secondly, they’re not aware of what happens. The most famous line of all is, “The owl of Minerva only takes flight at dusk.” It’s only at the end, that you get to piece together the narrative that you’ve been part of. But while you’re in the middle, you have no idea, and maybe you’ll disappear without a trace.

— Full interview: Marcus on philosophy as preparation for entrepreneurship

Progressivism needs moral substance

Colin Moran, Managing Partner at Abdiel Capital (top Wall St. hedge fund)

The progressive understanding of creativity puts an emphasis on novelty and newness. And they make the word disruption, which traditionally has had a pejorative character, have a positive one. So you can see in that the fact that disruption has been turned into a positive good. What we ought to be talking about is improvement. And they don’t. They use these words like effect. “Change” is a favorite phrase. And “disruption”.

So I think what I was getting at there is that progressivism in equating creative action with sort of change itself has too little connection to kind of an objective notion of good and too much of a kind of a worship of novelty. And you can see this in the buildings these people make. I mean, they kind of come out shiny and new. And then within like nine years, you’re wondering, why did anybody build this stupid warehouse-looking glass box? I mean, we could come up with examples all over the city, but novelty wears out fast.

And that’s, I think, the problem with this notion of creativity. You know, the Renaissance is a great example of a creative movement that saw itself as recovering something from the past. They didn’t aim at disruption, they aimed at recovery. And in the act of recovering, they created this incredibly fertile good thing that was both incorporating so many of the kind of achievements of antiquity, but which they gave kind of new expression to. That, to me, is kind of the ideal kind of creativity as opposed to this sort of thing that’s all about change and disruption and not enough about good.

— Full interview: Colin on faith, investing, and the humanities

Religious and secular worldviews might converge

Nick Bostrom, Oxford philosophy professor, author of Superintelligence

I think in general that there are strong parallels between the thoughts developed in religious and theological contexts, because it’s in some sense the same fundamental question - what’s the best possible future for a human being if you abstract away from various contingent limitations and constraints?

More generally, I think actually when you think through the full and ultimate implications of the standard physicalist worldview, and really think in many ways, you get to considerations traditionally developed in a theological context.

The philosopher Derek Parfit, who was a colleague at Oxford, had this metaphor in his work of a big mountain. And he did work on metaethics. And he had this view that different approaches to metaethics, sort of consequentialism and deontology, they were kind of climbing the same mountain from different sides, and that when you thought through each one to its kind of purest and clearest form, that they would sort of converge at the peak. And I think maybe there is like some similar phenomenon where you have a big mountain where people have been climbing it from the theological side, and if you climb it far enough, high enough from the naturalistic side, maybe you get to a similar conclusion in the end.

— Full interview: Nick on how to approach life in a ‘solved’ world

Philosophy can be co-opted as justification

Joe Lonsdale, Co-founder of Palantir and 8VC, among other companies

I tend to find that most people, if you’re not really contemplative and you don’t really challenge yourself, you tend to choose the philosophies that just naturally accompany whatever your biases are. And most people’s biases are to live a life of ease. And their biases are not to have to confront hard problems or be unpopular or fight the bad guys.

And so they end up choosing philosophies like “there’s no such thing as bad guys”. Like the average billionaire, if they wanna live a comfortable life, they say, well, there’s only so much one man can do. It can’t really affect history. There’s just these bigger systems. It’s all beyond me. So they become very cynical, very nihilistic, and if you wanna live a virtuous life, if you believe in the great man theory of history, if you believe that there’s impact we can have on the world, then it’s a very different set of things you force yourself to dive into.

— Full interview: Joe on the political philosophy that underlies his ventures

Wittgenstein is a guide to understanding consciousness

Murray Shanahan, AI researcher, emeritus professor at Imperial College London

I think Wittgenstein has a lot to teach us about consciousness in general.

Very famously David Chalmers introduces the distinction between the so-called hard and easy problems of consciousness. So the easy problem of consciousness is trying to understand the relevant cognitive operations that we associate with consciousness, such as the ability to produce verbal reports of our experiences, to bring to bear memory and so on… the hard problem is to try to understand how is it that mere physical matter, as it were, can give rise to our inner life at all, to the fact that we experience things at all. How does that come from mere physical matter? Because it seems as if whatever explanation we provide for all of those cognitive aspects is not going to account for this magical light that’s on inside me.

And so that’s sort of the hard problem. And earlier on you alluded to Descartes [who]… reduces everything and so pares away all of the physical world and leaves us just with the experiencing ego. And so in doing that, he’s carved the reality in two by saying that there’s this stuff out there and there’s this thing in here which is me and my ego. So he creates this dualistic picture. And this is what David Chalmers, when he talks about the hard problem, is alluding to. Now, so what does Wittgenstein teach us: Wittgenstein’s procedures, philosophical procedures and tricks and therapeutic methods enable us to overcome that dualistic thinking, much as Buddhist thinkers do, such as Nagarjuna.

— Full interview: Murray on AI consciousness

The Great Books are a training ground

Francis Pedraza, Founder of Invisible Technologies

[As 12-years-olds] in the first year, you’d read the ancient Greeks, you’d read Homer and Plato and Aristotle, and the next year you’d read the Romans and read Tacitus, et cetera. The third year, you read the Medieval Scholastics. Fourth year, you’d read a lot of the Renaissance enlightenment authors. And through the fifth year as well. And you’d read the whole book, not little excerpts. There was no textbook. You had to read the actual original text, the classics. And then you’d write essays and you’d listen to lectures and you’d debate the subjects.

They built the whole community around it. It was incredible. I got a better education in high school than I did in college. They taught us how to think. What’s so interesting is when you do this kind of an education, what emerges, they call it “the Great Conversation”. You end up realizing that for about 2,000 years, all of these authors have been responding to each other’s thoughts.

— Full interview: Francis on entrepreneurship, heroism, and spirituality

AI optimization causes moral atrophy

Brendan McCord, AI entrepreneur, founder of Cosmos Institute

The phrase I would stick in your mind is “Autocomplete for Life”.

We use AI systems to get the next word in the sentence... but also the next decision, the next job recommendation, the next relationship, the next purpose. And it feels very harmless. It feels convenient. But it adds up. It causes a kind of erosion of choice. When we offload, we atrophy. In other words, we lose the skill... If you lose self-direction, we cease to live fully human lives. We may act in the world, but it isn’t really our life to live.

Even if an ‘Omniscient Autocomplete’ could tell you exactly who to marry and be historically verified as correct... it would be ‘one thought too many’ to have an external agent determine that. We must have a capacity for reasoned self-direction. We can do it wrong, but we must preserve that space.

— Full interview: Brendan on how we retain human autonomy and thought

Philosophical questions are becoming experimental

Michael Wooldridge, Oxford University’s AI chair, multi-agent AI pioneer

This is really genuinely, I think, a watershed moment in AI history, because we have gone from a period where a lot of questions in AI were purely philosophical questions. They were literally reserved for philosophers until a few years ago. And suddenly, it is experimental science.

Are large language models conscious? Well, let us roll up our sleeves and do some experiments and find out. No, by the way, they are not. But these are now practical, hands-on questions. And to have gone from not having anything in the world that you could apply those questions to, to having actual practical hands-on experimental science in just a few years is mind-boggling.

— Full interview: Michael on the fascinating 100-year history of AI

Dynamism needs a rejection of incompetence

Michael Gibson, Co-founder of Thiel Fellowship + 1517 Fund, author

I think Girard is absolutely insightful when it comes to the nature of envy and motivation and desiring scarce goods, hierarchies of power, form and authority, and people are gonna fight and imitate each other and try to create meaningless differentiation to get to the top. But what we have to see: what makes a society more dynamic, what leads to better standards of living, greater scientific discoveries and cultural achievements, is somehow letting these hierarchies emerge and compete and always be contested.

And I’ll bring it back to the origins of Western literature, back to Homer. The fundamental conflict of the Iliad is not the battle, the war between the Greeks and the Trojans. I know that’s the setting and that’s why everyone’s on the battlefield. But the poem begins with anger expressed not at the Trojans, but at incompetent authorities and allies.

— Full interview: Michael on innovation and our education system

AI is propelling us into “moving history”

Tyler Cowen, Economics professor, public intellectual, Cosmos Founding Fellow

Think about your children. I think psychosocially it’s very disturbing that you can no longer tell people what kind of world they should prepare their kids or grandkids for. So my daughter, Yana, she’s 35. Basically, I adopted her when she was 12. She and I had a lot of discussions and I felt I could outline to her pretty clearly the world she would be starting work in and that it would more or less be just like the world when she was 12. There were differences, but you could make the same kind of plans and your plans would be completely fine. And indeed for her, they were, and it’s gone great for her. That’s just not true anymore.

Even take the best-case scenario, we will be stunned and shocked and disoriented. In some ways, the purely positive scenario might be harder for us than a mixed scenario. Because a mixed scenario, fighting off these challenges gives you something to do. Gives you a sense of meaning and purpose. If it’s only all positives, maybe that’s tougher mentally. So I don’t have real guides, but I tell people like invest in friends, great peers, mentors, and make sure you have some fun rewarding cheap hobbies.

— Full interview: Tyler on AI reshaping writing, economics, and conflict

Hegel shows the need to recognize others as individuals

Reid Hoffman, Founder of LinkedIn, founding board member at PayPal

In Hegel, we’re first born as a consciousness. We think we’re kind of a God in this world. Then we start encountering other things that aren’t objects to our use, and we first try to enslave them to be objects to our use. And then we eventually realize that they’re not actually objects, they’re other subjects. And we get into an intersubjective balance of identity.

We benefit enormously from these kind of challenges and frictions of diversity of other people, people who disagree with us, people who add something to how we become kind of our better selves. And sometimes it’s like a disagreement in worldview and ideology. Sometimes it’s an understanding of how to be more empathetic with other people. Sometimes it’s a kind of different experiences that you have in different cultures, different walks of life, the people who are less privileged, you know, all of this, you know, is an important part of how we evolve to be our better selves.

— Full interview: Reid on the social aspects of AI

Johnathan Bi competed in the Canadian Math Olympiad, studied CS & philosophy at Columbia, and was on the founding team at Opto Investments.

He interviews leading philosophers, technologists, and entrepreneurs. You can find him on YouTube and Substack.

Cosmos Institute is the Academy for Philosopher-Builders, technologists building AI for human flourishing. We run fellowships, fund fast prototypes, and host seminars with institutions like Oxford, Aspen Institute, and Liberty Fund.

The "Autocomplete for Life" fram really struck me. McCord's point about how offloading decisoins causes atrophy feels spot on, we're essentially outsourcing the very process that makes us autonomous. What's interesting is how this ties back to Marcus Ryu's observation about the first-person vs third-person tension. Maybe the real risk isn't just that AI optimizes our choices, but that it collapses that productive tension between subjective experience and objective reality.

Thanks for sharing. I may be wrong, but for Nick Bostrom, it sounds in the interview like he said “religious, uh, theological” and the “between” was just a false start. If that’s right, he would have been saying that there were parallels between deep utopia and theological/religious thought, rather than between theological and religious thought.